ITA: Scoperta, adjective -> ENG: Uncovered, Exposed, Defenceless, Bare. Antonym ITA: Coperta -> ENG: Covered, protected.

I always thought I was strong, like a Mediterranean pine. Hardy. That my desert blood fused with an Iberian hotchpotch of Castiglian mystery and Atlantic pseudo celticness had armed me with a special resilience. Turns out I’m vulnerable. Scoperta – uncovered, unprotected, and at times, very unprepared.

Algeria, October 2022

We are waiting for my suitcase. The domestic airport of Oran, nothing more than a glorified hangar in which friends, relatives and picker uppers are permitted to wait by the baggage carousels. The odd Touareg in fantastic desert turbans ignoring the no smoking signs with a Gauloise hanging out of the corner of their mouths; their swaddled heads cloudlike emerging among a sea of raven haired locals.

“She passed two days ago”.

It was my French doctor cousin speaking now, referring to his mother, my aunt. I had no idea her death would be so imminent. My father, her brother, stands silently with a blank expression. Arab men, weirdly nonchalant about death. A bandage covers up a Gorbachev-esque scar on his head from when he took a stumble the day before. The scar later morphed into the shape of Africa- a brutal branding, though fitting.

The only time I’ve heard Algerians owning their Africanness is with a deep sense of irony and as a way to deflect anything well below Western standards.

“Is it hot?” – I asked my dad on Whatsapp video chat before arriving“Hot?” Yes it’s hot. It’s like Africa over here!”

“We eat with our hands here, you don’t mind, do you Farida?”, asks a cousin at my aunt’s house. “We are in Africa after all!”

“How come there’s no signal here?”- I ask another cousin. “Ha! Welcome to Africa!” is always the knee jerk response to cover up their shortcomings, their inability to move forward, their post-decolonialised trauma.

“Have a look around! Oran is better at night – it covers up the dirt!”.

Still my doctor cousin – now in the car on the drive back from the airport into town. It was actually my second time back in Algeria. We are going straight to my aunt’s house; his late mother. We arrive at Rue de la Vielle Mosquée opposite the French consulate which resembles more of a military compound. The French have barricaded themselves in and closed off the road. Beyond the high walls you can see new builds; European style residential complexes so they don’t have to actually live among the locals and the filth and the cats yet remain in the real centre-ville. Yet for all their seclusion and exclusion and modern living quarters, they can’t escape the call to prayer every morning at 5am from the mosque opposite. I kind of liked that. Their military cover does little to shield them from reality.

We approach the apartment building door under the cover of darkness like a stealth squad- a cluster of folks are drinking tea and smoking on the street outside. I quickly piece together they must be mourners. Bonsoir Farida, I hear one of them say. I turn around and look at him blankly. He has to introduce himself…I narrow my eyes and take a closer look; it’s my long lost Dutch cousin- one of the lucky cousins who made his way to Europe- Rotterdam specifically and made a success of himself. I hadn’t seen him since I was ten years old at his wedding in Gouda. Condolences, kisses, hugs, apologies for not recognising him. All in crossed tongues, English and French clumsily tumbling out.

We enter and go up the unlit stairwell to my aunt’s apartment. Memories of the tiles and the layout of the flat the last and only time I had visited 6 years prior come flooding back. The disposition- so cleverly organised so as to benefit from the sun whilst ensuring maximum shade. My father said that this row of buildings was a largely Jewish quarter in the past. He’s always telling me what and where used to be Jewish in Oran. Their absensce, as with so many things in Algeria, clearly a sore point.

We reach the top of the stairs and I’m greeted by my teenage cousin, now 23 but a still a teenager to me. Still looks the same, slightly heavier, more beardy. My cousin, he calls to me. It’s very sad. But c’est la vie. I’m filled with empathy; his grandmother, my aunt, was his second mother. I hug him. We enter and I’m enveloped by a flurry of veils and arms and tears and kisses and warm smiles. She loved you very much, they tell me over and over again in French. I am happy to see them I realise, but cry too.

Soon we are sat in the living room huddled round low tables eating dates and harira soup, followed by sharing bowls of cous cous. Food, forever binding people together in times good and bad. More of a social glue than a source of comfort.

The flurry of veils is a relatively new thing in my family.

Before they were largely unveiled, like me. Exposed. The decision to cover up is complex. Tradition, societal pressures, conforming. Take your pick. It’s a woman’s choice. But choices are limited in this part of the world. So you make the best with what you’ve got.

I organised my wardrobe to fit my environment a lot more conscientiously this time. I realised I’ve developed a sensibility and awareness for it now to fit the modesty aesthetic that so prevails. It’s different from that of the gulf states (which relies heavily on an Arabian princess aesthetic), and it’s not too difficult to get down once you have a few key pieces in your wardrobe.

A couple of maxi skirts, some feminine long sleeved or mid-sleeved cotton blouses, loose fitting linen all in ones with an oversized cotton short, wide legged pants, a lightweight linen blazer. A trusty cotton scarf on hand always.

The more days I spent in Oran, the more I felt the urge to cover my hair. Not so much to fit in with the veiled ladies and the prevailing Muslim culture, but more as protection from the god-awful smog and polluted air. It was practical- the same with the long sleeved, loose fitting clothing. You’re better off covering up a bit in that heat. It’s textile based sun protection. And there’s something to be said for wearing a long dress and weaving your way through the often filthy market streets, having to hoist it up over your ankles as you jump over mirky puddles of water collected in the uneven cracks and numerous potholes of downtown Oran. It makes you feel ever so dainty. And it’s an achievement to be able to get home without any backsplash on your trousers. I never fully committed to going fully veiled, but I made a nod in that general direction by loosely draping a scarf over my head with fringe still fully visible- giving BBC correspondent Lyse Doucet in Afghanistan vibes.

The driving force behind my second visit was to go to the desert. Specifically the Saharawi refugee camps stationed in the southwest corner of the Algerian Sahara, where I would stay with a host family.

Western Saharans, still awaiting sovereignty, began to flee into neighbouring Algeria to escape Moroccan attacks and occupation as early as the 1970s. The Algerian state welcomed them and set up what were supposed to be temporary camps in the area surrounding the military town of Tindouf in south-west Algeria.

Decades later, camps have taken on a more permanent desert town appearance. Tents have been replaced by concrete shacks covered by sheets of corrugated copper roofs held down by nothing but desert rocks. The slightest drizzle, though rare, sounds like a biblical hailstorm. I went there on a volunteering mission to offer teacher training and English lessons. It was one of my 2020 plans scuppered by the pandemic and I was so happy to have it finally come into fruition.

While these makeshift desert bungalows are comfortable (palatial at times), they are by no means impenetrable to the likes of desert scorpions and a host of other noxious insects. One day I awoke to three very evenly spaced out bite marks on my forearm, and three more on my neck. I was also extremely tired, numb down the left hand side of my body and had an annoying sense of pins and needles in my left hand and creeping up my wrist. I was taken to the clinic and then referred to the Cuban-run hospital in a neighbouring camp. My symptoms were not consistent with any bug bites they knew of, and my sleezy Cuban doctor, more interested in flirting in Spanish with a bare armed and unveiled westerner than doing any real diagnosing, prescribed me rest and multivitamins.

The camps (five in total) are spread out through the vast and seemingly endless Algerian desert where the borders line up with Mauritania to the south-west and Mali directly south. Protection out in this semi-wild, old testament-esque desert wilderness is present in the form of checkpoints on entry and exit. Any outsiders are welcome by invitation only, followed by approval from the local government (called the Polisario.) An entourage consisting of Polisario officials and the Algerian military police will escort you both in and out. At least this is the drill for all foreigners entering with N.G.Os. Algerians, technically on home turf, are subjected to slightly less stringent procedures. In my case, wielding an unholy trinity of Spanish, British and Algerian passports, I encountered several diplomatic glitches. Which protocol exactly did I fall under? A lifetime’s worth of identity crises now a very real and headscratch-inducing conundrum. Eventually, after getting over the further confusion of my not speaking Arabic, the Algerians assumed responsibility for me. She’s one of us, she’s one of our own! they reassured themselves as they hopped back in the Gendarmerie Land Cruiser, and lead the convoy consisting of me (and my local driver), deep into the desert, covered and protected by my brothers of green and white and red crescent moon and star.

As you head further and further south into the depths of the desert, the need to cover up is just good common sense, it being a harsh landscape brutally exposed to the elements.

The traditional and mainstay covering-up garment of Sahrawi women is the mihlfa. It consists of a two to three metre stretch of fabric loosely wrapped and draped around the female form – an underdress and or leggings are worn underneath. Additional head fittings will be worn under – though not always, with the inclusion of gloves – all to keep the skin firmly shielded from the harsh and ageing sun. The myriad of uses; from swaddling clothes to throws and picnic blankets, and the full spectrum of colour and patterns add to their unique identity, and joyfully break the visual monotany of sand yellow and sky blue. Young girls go veil-less and Western-style casual until they start menstruating .The societal convention to cover up from the moment they start to bleed an indication that they have entered womanhood.

The six year old daughter of my host family, still very much in her carefree veil-less days, would hide up inside my scarf as we would walk home from school. Her little face, so much closer to the ground than mine, would seek refuge inside my scarf and under my arm, protecting her from the gusts of wind that whipped up sand into her large brown eyes.

In that brief time, it occurred to me that I had never been around that many children at once in my entire life. From the countless cousins, nephews and nieces playing in and around the kibbutz style housing arrangements, to the school I would visit everyday for lessons and teacher training. Where children routinely sprint towards you for unsolicited and long, enthusiastic hugs; perfect little packages of pure effervescence and joy. I found myself, late at night, lying alone in my surprisingly comfortable room, while my host family slept together out in their garden under the moon, (stars less and less visible because of the light pollution), aching for a small person of my own to protect. It was deeper than the pangs of nostalgia for being a small child and missing my mother, as she was, younger than myself now, looking after me and taking me home to Spain and to the beach to bask in the waves. This was a distinct and deep yearning from the pit of my being.

Rome – London, summer 2020 – February 2023

I chose not to confess any of these nocturnal yearnings to my partner when I returned to Italy. He did, however predict, when I suggested we try to guess each other’s new year’s resolutions, that I might want to have a baby this year. I told him that having a child wasn’t really a resolution- I was merely attempting some lighthearted dinner banter, but he pressed me and asked if it was true. I struggled to answer but my eyes betrayed me.

Not long after at lunch one day he blurted out:

Se vorresti avere un bambino adesso sei completamente scoperta. If you wanted to have a baby now, you’re simply not covered. Non potresti avere la maternità con il lavoro che fai. You wouldn’t be able to get maternity pay with the job you have.

He broke up with me three weeks later, despite us having previously named our unborn children.

That wasn’t why our relationship imploded, though it certainly didn’t help.

We met in October 2020- the tail end of the summer of fun after the first heavy lockdown of spring. It was a brief window of “normality” – so long as you were vaccinated and wore a facemask in public. His face was entirely covered when we met for the first time. Black sunglasses hid his small chocolate brown eyes and a black facemask hid his strong nose, crooked smile and standard issue beard. I motioned for him to bare his face and he did so bashfully. I liked him and listened attentively as he overshared details and frustrations about his current life. I appreciated the frankness, but my instinct told me guys like this … guys like this don’t really go for girls like me. One week later, the country went back into semi-lockdown and nightly curfews and we clung to each other for dear life.

Two months before it ended, I learned that my immune system is at war with me.

Its specific beef is with myelin; a substance which protects the nerve fibres in the central nervous system. But my body, for reasons unknown, is hacking it off my nerves either slightly or completely, leaving in its wake battle wounds known as lesions.

The condition is called Multiple Sclerosis. Exhaustive tests back in London confirmed it after my trip to Algeria, and it was the reason why the original numbness and the tingling from the desert had still not left my body.

No one really knows why MS happens, but not surprisingly, stress can be a major trigger for relapses and episodes. The central nervous system; our very own internal intergalactic highways running through our very own corporeal universes, needs to be kept on side. It has to be regulated or it will turn against you.

Despite reassurances from people who claim to know people who have it and “it’s absolutely fine, you’ll be fine!”, it scares the crap out of me. “It’s a lot to take in, isn’t it? But don’t worry; treatment is really good these days”, has been the standard NHS nurse response, in that very pragmatic way of looking at things that I have come to miss tremendously living away from England.

Back in London in the summer of 2020 when we had spent the best part of four months with our faces covered, I started to lose vision in my left eye. It was optic neuritis and is often the first tell tale symptom of MS.

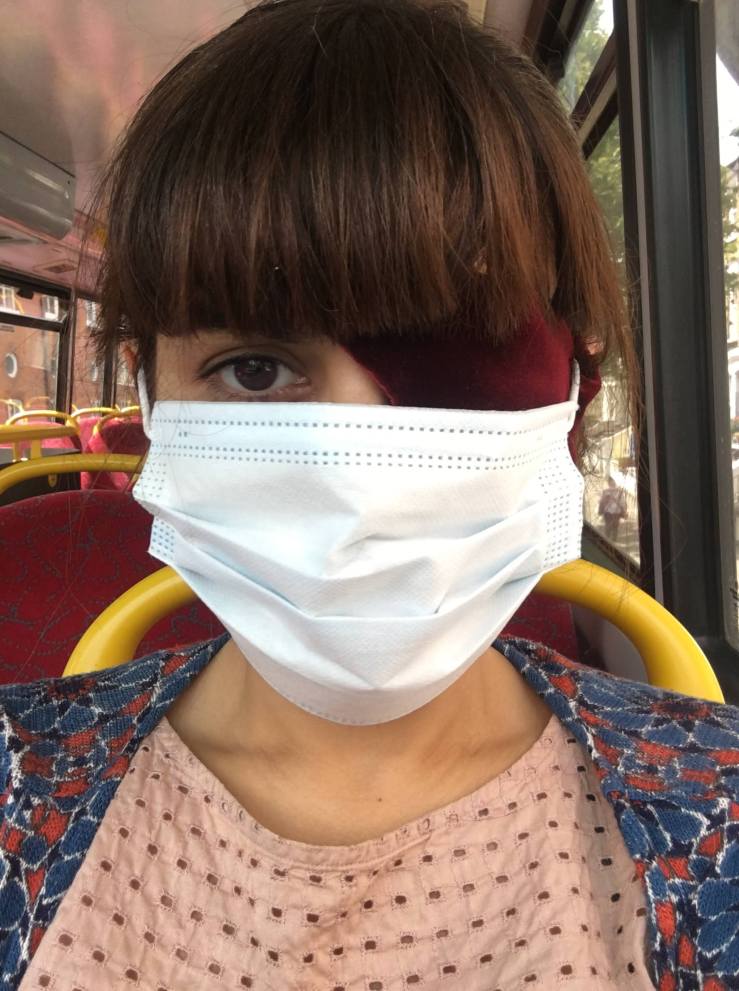

With daily doses of steroids, my optic nerve inflammation gradually went down, but using the eye itself brought on headaches and nausea, so I resorted to covering it with a homemade, red velvet eyepatch. In those days, face coverings were still mandatory in all indoor places and so for a brief period, I was seen to have about 80 percent of my face covered, when you take into consideration my fringe which covered my forehead too.

Two years later, I was living in Italy. It was May 2022 and the requirement to wear facemasks indoors had just been lifted. I was teaching English at a high-school in central Rome that year in the afternoons, and decided to have breakfast somewhere first. Going past all the bars and taking the metro, it was strange and a wonderful relief to feel exposed again, and to see everyone once more unveiled and vulnerable almost; like my poor nerves fending for themselves without their myelin sheath.

I went to a cafe by the Circus Maximus, and for the first time in two years was greeted with big visible smiles by the waiters which I enthusiastically returned. I ordered a cappuccino and a pastry which they brought to my table. The waiter had written”bella” in chocolate sauce on my cappuccino foam and I welled up. A syrupy celebration of my uncovered face.

For once, it was good to be Scoperta.

Leave a comment