Sta arrivando! “It’s coming!”, the man from the ticket office says in reference to a bus that was supposed to have arrived thirty minutes ago taking us from Catania Airport to Siracusa. Though it was my first time on the island, I understood immediately that this would not be the first time I would hear these words in Sicily, and so I rejoined my mother on the bench by the bus stop and waited. Some locals looked at us and then to each other, and with a sigh said pazienza…” patience”. It was clear. There was nothing else to be done, so we waited.

Sto arrivando! “I’m coming!”, says Angelo, six weeks later over the phone at 11:40pm after what was supposed to be a 10pm date. Less patiently this time, I said OK and hung up the phone and continued to wait. He had fallen asleep, he says, after taking a shower while he was getting ready to come and pick me up.

It was in Sicily where I practiced the art of waiting patiently, and rediscovered my admiration for the profession of waiting tables; for those who have made it their occupation to wait on people.

I’m no stranger to the southern European way of life. I spent all my summers in Spain. I remember as a very young girl, perhaps no more than six years of age, going into bars and cafes with my mother and relatives and being sat up on bar stools where, clean-cut swarthy men with slicked back hair, in impeccably clean white shirts would address me as señorita, guapa and bonita, look me directly in the eyes (my big beautiful eyes as they always told me) and ask me what I wanted- just as they would all the grown-ups. They would hit me with great lines, in dialect no less like nun te manques, con esos güeyos que tienes tan grandes, o? – “Don’t you ever hurt yourself with the size of those eyes you’ve got there?”.

Enjoying myself tremendously and yet taking it very seriously as my mother reminds me now, I would look them square in the eye and order my drink of choice which at the time was a sweet apple juice called Trina de Manzana. I believed them when they told me I was beautiful, as I believe them now because it’s their job to make me believe that- whether they are being sincere or not. It’s part of the theatricality of it all. We all have our parts to play and I am happy to play along.

And so these exchanges I had as a young girl, one where dark-eyed men smiled, complimented me and then asked me what I wanted were very probably among the first sexual experiences of my life. Or at the very least, triggered a fledgling sexual awareness.

But this isn’t about me documenting any particular fetish of mine. If you want to throw more logs onto that Freudian fire, my father was a chef.

This is about respecting and honouring a trade, an art even. One that so often doesn’t get the respect it deserves.

It’s about the professionalism, the grooming, the agility, the memory, the charm, the attention to detail. The obligation to put up with people’s shit. Underpaid and overworked; waiters are tested day in day out, and if you want to keep your job in Sicily, you had better be good.

Tourists don’t much care for Catania. They find it dirty. Unsurprisingly. They will most likely have just come from the resplendent Ortigia or picture-postcard perfect Taormina. On their pre-paid organised tours they are advised by their tour operators to spend no more than a day in Catania; to sample the food for which it has a well-earned reputation, before rising early the next day for the obligatory trip to see the mighty Mount Etna.

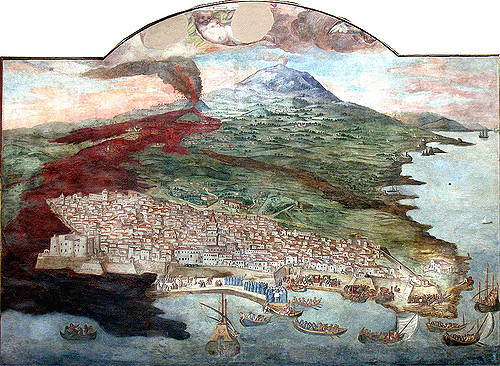

Catania is grey- also unsurprisingly. It was rebuilt after the devastating earthquake of 1669 from lava stone, the very lava that engulfed the city, spilling down onto the coast line killing thousands. The city’s paving stones are bulky, black and uneven made from the same deathly but durable lava.

Notwithstanding, it is also grey from the pollution. An ill-advised decision to get rid of the tramway which once graced the city’s central avenue Via Etnea, continuing all along the once industrial seafront and port, means that locals today use their cars not merely due to the Italian obsession with them, but out of necessity. Buses exist but as an improvised after-thought. Then there’s the ubiquitous graffiti; the occasional refuse collection strike, the abandoned and defiled baroque palazzos and industrial buildings, the anarchical parking system …the list goes on.

To my mind however, it is the day-tripping tourist, with their lamentable fashion sense and bumbling pace who litters the city far more than any disenfranchised youth with a spray-paint can and a devil-may-care attitude to waste disposal.

The only line of defence against this daily onslaught of scantily-clad and unappreciative tourists, often spending as many Euros as items of clothing on their person, is the service industry. It is the waiters who, with painted smiles and feigned exuberance practice their pigeon English with bemused Euro types and American pensioners. From them they expect or at least hope for a tip, which all too often isn’t generous enough after they have consumed their guidebook advised arancini, granite, cannoli; crossed them off the checklist and moved on. The kind of tip that would never be left by a local for whom eating and drinking out is a daily activity, and so tipping would therefore add a significant outgoing to the monthly budget.

Though it goes without saying that the best waiters, regardless of where they are from are the ones who know how to be attentive and present and yet maintain their distance.

The flare, the theatricality, the efficiency; I am forever in awe because I know that it is not just an act for the undeserving tourist. They are doing this on a daily basis for locals too. I think nowhere do they understand the importance of this more than Italy.

Once in Naples, with another Sicilian suitor (though not a waiter), we were having dinner and paused our conversation to listen in to the little scene playing out at the table behind. Two waiters were attending to a table of six, serving desserts; an array of gelato and cakes and limoncello; I had my back to the scene but surmised from the conversation taking place that the younger waiter must have been a bit slapdash with the way he was laying them out on the table, as the other more senior waiter was kicking up a fuss, and in jocular fashion admonishing him, declaring no no no, così non può essere! Con amore ! Con amore! , “No, not like that..with love! With love!”. We had to pause a moment to appreciate the scene, and the joy that it brought not only to the table of six but to us and presumably anyone else who was within earshot. And we proceeded to discuss what makes a good waiter and why and how important and it is to show courtesy and professionalism.

My first foray into Sicilian life was shortly after the disastrous end of a long distance relationship, and so inevitably, I had an affair with an Italian waiter.

I was, for the first time in a long time, free and most definitely vulnerable although I didn’t realise how much at the time, and the whole thing was so natural and easy. I remember he drove me to the airport in his Fiat Punto at the end of my five week stint in Sicily (the first of many stints), and he brought with him an arancino and a cake from the bar where we met for the journey. My favourite kinds of arancino and cake. Needless to say, he already knew. He was an attentive waiter. And much like his profession, at which I think he excels; as a boyfriend he was also attentive and yet he kept his distance. No lengthy phone calls or daily texts; he hated mobile phones. But he was there; he told me I was beautiful and he knew what I wanted.

On his evenings off, we would go for a drive and have a bite to eat or an aperitivo, and we always spoke of the waiters; who was good, professional and why.

Behind the scenes, back at his modest apartment; I saw the lengths he went to in order to appear smart, clean and well-groomed. One morning he was running late and asked me if I wouldn’t mind ironing his shirt while he jumped in the shower. I told him I wasn’t very good at ironing- my mother did my ironing and then after leaving home..I guess I never really needed to iron anything all that impeccably- just a quick going over if ever I was really going to trouble myself.

In any case, I nervously took the freshly washed white uniform shirt; splayed it out onto the board; desperately trying to remember my mother’s instructions (in Spanish)- do I start from the collar? Why? Wait, when do I do the sleeves? I did the best I could and hung it up on a hanger, sitting eagerly on the bed waiting for his approval. He came back into the room, saw the shirt, smiled and said nothing. But patiently took it off the hanger and splayed it back onto the ironing board and proceeded to give it a good ten minutes’ worth of serious going over. Steam rising from the shirt as he industriously and powerfully eliminated every single crease until it looked brand new.

A holy baptism of iron and steam; that shirt was crisp and spotless. And I hung my head in shame as I watched him do it and said ti avevo detto che non sono brava…. “I told you I was no good”. The Catholic undertones were not lost on me.

Then the hair. Blessed as he is and as are many southern Europeans with wonderfully wavy, mahogany brown hair with auburn undertones- he would on a monthly basis go to the salon to have it relaxed and then, just as with his shirt- he took a metal comb and with concentration and purpose, straightened it out with gel for that classic slicked back look I’ve known of since my childhood.

Shoes polished, Ray Bans on; it’s time to hit the street. He needs to be there by 7am. I kiss him goodbye just before he goes in, and feel guilty all the way home knowing that 1) I can’t iron a shirt to save my life and 2) he’s going to work like a horse all day looking immaculate while I go home and have a nap, and then later in the day teach English via Skype (dressed from the waist up) for a couple of hours. And the worst of it all is that at the end of the month, we will probably have made the same amount of money.

The injustice still smarts to this day.

Waiters are on the frontline, they are our unsung heroes. When the Apocalypse comes, they’re the ones I’ll rally up first. At the very least, they’ll be able to fix you a decent drink.

Leave a comment